Article by Kitty Currier, graduate student at UC-Santa Barbara [currier (at) geog.ucsb.edu]

(Editor’s note: The CGA thanks Ms. Currier for providing this excellent article and making the related resources available to our members. We welcome submissions from any CGA member or geography educator who would like to share a lesson plan or learning activity.)

Leather craft, archery, and sheep showmanship were activities I pursued as a youth member of the All-American 4-H Club of Fort Collins, Colorado. Rooted in an agrarian past, the youth development organization 4-H has since expanded its focus to include the STEM disciplines—science, technology, engineering, and math—in its mission to foster leadership, citizenship and life skills in children. “Maps and Apps” was the national 4-H science theme of 2013, recognizing that geospatial technology and reasoning skills are essential to many of today’s careers and approaches to solving problems.

To align with the “Maps and Apps” theme, members of UC Santa Barbara Geography’s Outreach Committee and the Center for Spatial Studies developed and delivered the workshop Building a UCSB Scavenger Hunt. Following the 4-H “learn by doing” approach, the workshop was designed to teach participants how to read and navigate with a map, use a GPS receiver to collect geospatial data, and visualize their data using Google Earth. Approximately thirteen 4-H members ages 9–16 participated in the workshop, which was held on three consecutive Saturdays on the UCSB campus.

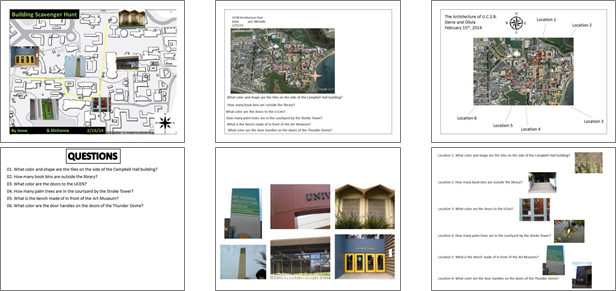

Each day had a different focus, beginning with basic map reading and culminating in the final project—a scavenger hunt, designed and created by the participants, themselves. On Day 1, participants followed self-guided tours adapted from UCSB’s Interactive Campus Map (http://map.geog.ucsb.edu/). Day 2 was devoted to data collection, where participants selected and navigated to different locations on campus; recorded their latitude–longitude coordinates using a GPS receiver; devised trivia questions; and shot descriptive photographs. Participants synthesized their data on Day 3, when they were tasked to design their own scavenger hunt in pairs. Each pair developed their own design that included a map created in Google Earth, trivia questions, and photos, all assembled on two letter-sized pages.

Post-workshop feedback from the participants was positive. The highlight of each day was the activity session (i.e., map navigation, collecting data, and producing paper scavenger hunts), but from a teacher’s perspective, the discussion, presentations and individual writing time helped participants realize that they were learning skills in addition to having fun. An important component of the workshop was the paper scavenger hunt that each participant brought home on Day 3, which they could share with their families and friends as a product of their own making.

One challenge that we anticipated was the range in age (9–16) of the participants. We designed the workshop to require no prior knowledge of the material, but inevitably participants arrived with different levels of competence. The age range turned out not to be a problem, however. As members of the same 4-H club, the participants all knew each other, and the older participants were used to mentoring the younger ones. If this workshop were to be delivered to a group of participants who were not as comfortable working together, however, such a difference in ages might pose a greater challenge.

Following are guidelines, templates, and our “lessons learned” for anyone wishing to adapt and offer a similar activity. More complete information about each day’s activities, along with a comprehensive materials list, can be found in the included example files, noted in red.

Schedule, Locations & Example Files

Day 1: Introduction to Map Reading (lecture classroom & outside)

Day 1_outline

Day 1_UCSB campus map

Day 1_UCSB walking tour example

Day 2: Field Data Collection (lecture classroom, outside, & computer lab)

Day 2_outline

Day 2_gps

Day 2_photos

Day 2_questions

Day 3: Mapping with Google Earth & Creating a Scavenger Hunt (computer lab)

Day 3_outline

Day 3_google earth exploration

Day 3_plain UCSB basemap example

Day 3_scavenger hunt template

Personnel & Structure

Four graduate students developed and led the workshop, which was attended by 6–13 participants each day. On days 1 and 2 an additional one or two adults assisted with the outside activity. Each day was allotted three hours and consisted of (a) an introduction to the day’s topic, given by the leaders; (b) a hands-on activity, where the participants practiced a skill; and (c) reflection and writing about the day’s activities. The structure was partly dictated by the 4-H program’s emphasis on presentation and record-keeping skills.

Budget

Our total budget was approximately $150, the majority of which was used to purchase four secondhand digital cameras and storage media. We borrowed GPS receivers for the activity at no cost from the Department of Geography.

Lessons learned

> Use existing campus maps & tours as resources when possible (e.g., for Day 1 map-reading activity).

> Be ready with an activity for the start of each day to occupy participants who come early; inevitably, some participants will arrive late.

> Have on hand participants’ parent/guardian contact information and relevant medical history/needs.

> Be prepared for fluctuation in attendance, and ensure that your plan is flexible enough to accommodate participants who miss a day.

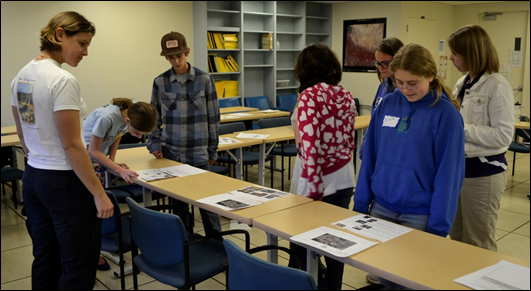

Figure 1. Day 1, ready to go! (Photo credit: Erin Wetherley)

Figure 2. Marcela teaches some map basics. (Photo credit: Erin Wetherley)

Figure 3. Participants study their GPS receivers. (Photo credit: Kitty Currier)

Figure 4. Participants explore Google Earth. (Photo credit: Haiyun Ye)

Figure 5. Kitty, Susan, and participants inspect the final scavenger hunts. (Photo credit: Haiyun Ye)

Figure 6. Three distinct approaches to scavenger hunt design.