The Houston Metro area and large areas of southeast Texas have been devastated by record flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey. There was tragic loss of life, and astronomically expensive damage to property and infrastructure. There will be a lot of discussion about how more frequent severe storms are a part of global climate change, and we can also focus on the science of weather forecasting, which continues to advance with new computational models and satellite data being utilized. But a very important point for us to reflect upon is how we could have done a better job of planning how we built our cities and infrastructure to protect against this loss of life and costly damage to property.

The fact is, catastrophic flooding in the Houston area was a highly predictable event. The National Flood Hazard Map maintained by FEMA can be viewed online here. Once the map is open, you can type “Houston” into the search bar in the upper right and zoom into the area most affected by the storm. You will need to zoom in further to see the specific flood hazard zones displayed. Pan around the city, especially to the west of downtown, and note the areas of 1% and 0.2% annual risk of flooding. That corresponds to the so-called 100-year and 500-year flood events. After a flood in 1935, channels and reservoirs were built around Houston to try to control flooding, and areas prone to inundation were identified. But Houston continued to grow and much of this growth extended into wetlands and low-lying areas where the risk of flooding was high. Gradually more was understood about the area’s hydrology, and it became clear that the reservoir system would not be able to protect the city from a “probable maximum flood event.”

So why was Houston’s development allowed to proceed directly into the area of greatest flood hazard? The economic imperatives of growth and the desire to provide affordable housing for a booming population overwhelmed the scientific evidence about risk, and the region’s leaders allowed developers to build and profit where they Now the chose. Excellent stories in the Atlantic, New York Times, and Wired provide a more thorough analysis of the problem, which they describe as a design problem and not a weather problem. Now Houston — the people as well as local, state and federal governments — must decide how to rebuild the city and whether to use what they know now to lessen the risk of flooding faced by future Houstonians.

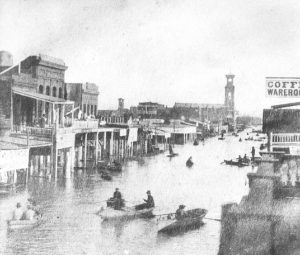

We aren’t at risk for something like that happening in California though, are we? Actually, California experienced an even more incredible flooding event – back in 1861-62. It is called the California Megaflood. You can read about it here. “A 43-day storm that began in December 1861 put central and southern California underwater for up to six months… This disaster turned enormous regions of the state into inland seas for months, and took thousands of human lives. The costs were devastating: one quarter of California’s economy was destroyed, forcing the state into bankruptcy.” This flood was associated with a phenomenon known as an atmospheric river, and California and the west coast continue to be at risk for this kind of storm event.

Go back to the flood risk map and type Sacramento into the search bar. You can see how the flood risk has been mitigated by the building of levees, as the flood risk in Houston was mitigated by the building of channels and impoundment reservoirs. But are the levees we built in the past sufficient to protect us from the storms that will come in the future? This is a vitally important question, and we need geography to be able to analyze the risk and develop plans that protect people and property.